June 2025

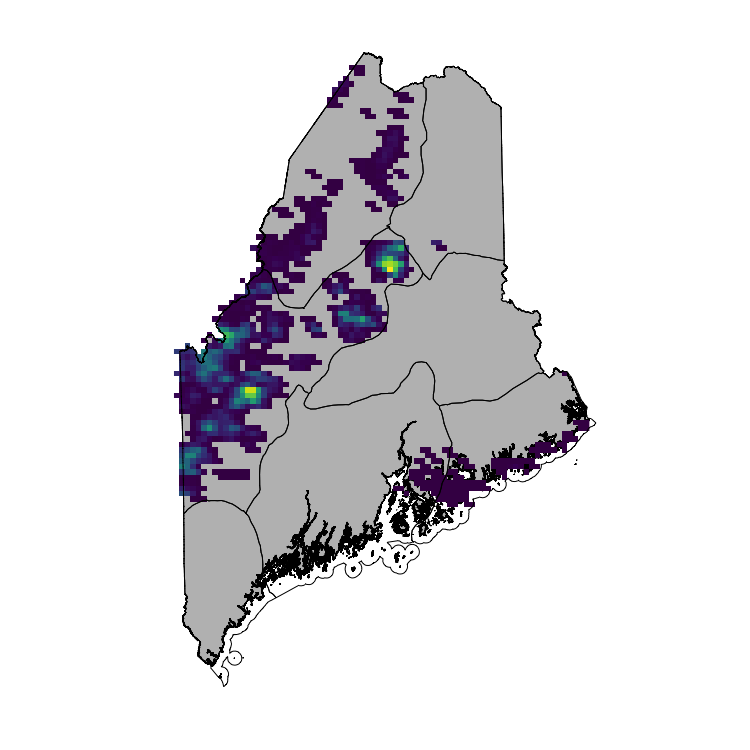

As a trailing-edge population, defined as those near the southern margin of a species’ range, Blackpoll Warblers (Setophaga striata) in Maine breed in habitat islands of cool, spruce-fir forests. Unlike other boreal forest-breeding songbirds whose breeding ranges in Maine often form an arc across western, northern, and eastern Maine, Blackpoll Warblers have a markedly disjunct breeding distribution in which the highest densities occur across the western and north-central mountain chain, while lower densities occur along the Downeast coast (Figure 1).

Between these two regions, considerably more research on this species has been conducted in their mountainous breeding habitat. Mountains exhibit a number of interrelated environmental gradients across an elevational range that can influence species distributions, including temperature, habitat, and biotic interactions. Blackpoll Warblers’ lower-elevation limit in these zones is likely driven by some combination of these factors where temperatures become too warm, spruce-fir boreal forest transitions to northern hardwood forest, and the abundance of nest predators, such as Red Squirrels (Sciurus vulgaris), increases (Ralston et al. 2019, Hallworth et al. 2024, Hill and Williams 2024, Warkentin et al. 2025). Monitoring of high-elevation breeding birds, including Blackpoll Warblers, in New England has been ongoing for the past 25 years through the Vermont Center for Ecostudies’ Mountain Birdwatch community science program.

Despite the recognition since the early 1900s that Blackpoll Warblers also breed on wooded islands in Hancock and Washington counties (Knight 1908), this region of the species’ breeding range has received comparatively little attention. Historical accounts of breeding Blackpoll Warblers in Maine often list more mountains than islands where Blackpoll Warblers are known to breed. For example, Knight (1908) mentions Mts. Abraham, Bigelow, and Katahdin in his county records, but with regard to island breeders, he simply states that the species “breeds on many of the wooded islands” in Hancock County. In the more recent Birds of Maine, Vickery et al. (2020) lists summer Blackpoll Warbler records on Mts. West Kennebago, Old Speck, Sugarloaf, and Coburn, but only lists one summer island record on Monhegan Island. The island record occurred on June 3, 2007, which makes the breeding status of the record unclear given that migrants can be found through early June. Other historical texts include a few additional breeding islands, including the Duck Islands (Palmer 1949, Bond 1971), Mount Desert Island (Bond 1971), and Marshall Island (Goodale 2009). The forthcoming second Maine Bird Atlas includes probable or confirmed breeding records for Blackpolls Warblers on three small, forested islands in the Great Wass Island archipelago—Plummer, Inner Sand, and Outer Ram Islands. While this warbler species breeds at lower densities along the eastern coast than in the interior mountains, comparisons between the regions are difficult due to the abundance of small wooded islands that potentially contain suitable breeding habitat but are relatively difficult to survey widely.

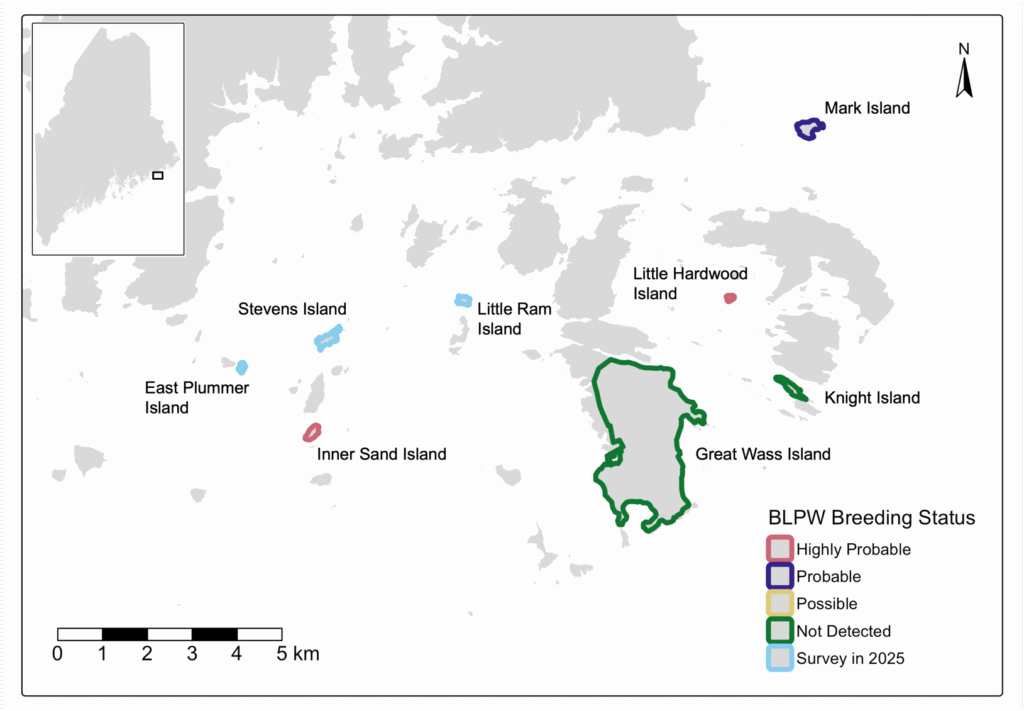

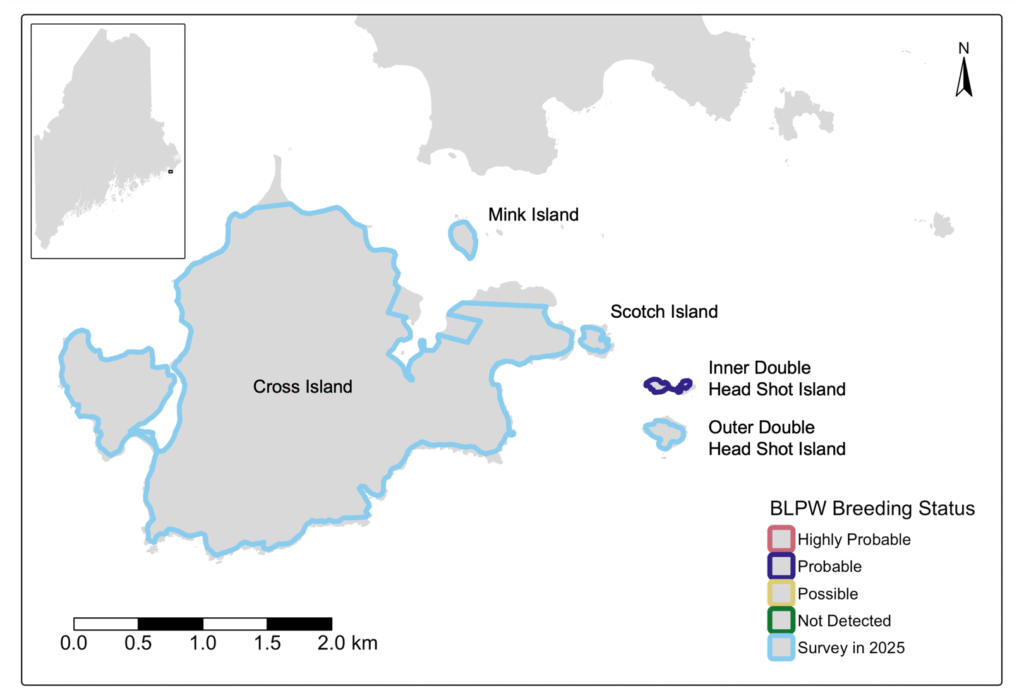

Maine Natural History Observatory launched an island songbird project in 2024 to better understand the community composition of breeding birds on islands along the Downeast coast ecoregion. While the project examines the larger breeding community, Blackpoll Warblers are the focal species of the project and have informed many of the survey locations over the first two field seasons. We deployed autonomous recording units (ARUs) on 17 islands and one headland between late April and early September 2024, with sites having one, two, or three ARUs based on their size class. We used male song as an index of breeding status given song’s role in pair formation and territory defense. A species detected once during the breeding period (June 10–July 21) was considered a possible breeder. A species detected multiple times at an ARU at least 7 days apart was considered a probable breeder. In contrast to eBird, we added the condition that the nearest detections must be no more than 14 days apart in an effort to retain only species that had a relatively consistent local presence indicative of a breeding territory. Confirmed breeding was impossible to assess with audio-only data, and so we created a ‘highly probable breeder’ category that was defined as a species with detections on at least 11 days in any rolling 14-day window (~80% daily detection rate). This threshold was arbitrary and not based on any analysis, and future work could compare different thresholds for defining high-probability breeders with audio-only data. To assign bird song to species, we used BirdNET—an open-source machine learning classifier—and validated a subset of detections for each species. Across the 18 sites we surveyed in 2024, Blackpoll Warblers were classified as highly probably breeders at two sites (Inner Sand Island and Little Hardwood Island) and probable breeders at two additional sites (Mark Island and Inner Double Head Shot Island) (Figures 2 & 3). All of these islands are small islands (1.6–14.2 hectares) and three are in the vicinity of the Great Wass archipelago. Breeding Blackpoll Warblers were not observed on larger islands (18.6–565.1 hectares) or the coastal headland site, although larger sites were comparatively undersampled and require more intensive sampling to more definitively establish absence of breeding. In spring 2025, we deployed ARUs on 13 new islands, 1 new mainland site, and 5 islands from the first field season where Blackpolls were present during the breeding period.

With only one field season of data and several more planned, it is premature to make any conclusions about the ecology of island-breeding Blackpoll Warblers in Maine. However, we can share some early hypotheses about this system that we can hopefully test as more data are collected. In the second Maine Bird Atlas, the three island records of probable or confirmed breeding for Blackpoll Warblers contrast sharply with the absence of a single record of possible breeding on the mainland coast between Schoodic Point and West Quoddy Head. All coastal observations in this region were during spring and fall migratory periods. This distributional pattern is certainly not for lack of survey effort; the Black-throated Green Warbler (Setophaga virens) atlas map shows a dense spread of observations with possible breeding status or greater along the entire Downeast coast. Based on both historical and contemporary data, it appears that coastal Blackpoll Warblers in Maine have an affinity for breeding not simply along the coast, but on small wooded islands specifically (we are ignoring Mount Desert Island for the moment as it’s an outlier that includes both montane and coastal habitat characteristics). The same environmental factors that determine the species’ lower-elevation margin in the mountain system should be considered in the island system too. For temperature, small Downeast islands—surrounded by cold ocean waters—likely provide this species with moist, cool breeding conditions that are absent in larger landmasses that heat up more during the summer. However, this climatic hypothesis does not explain why Blackpoll Warblers appear to avoid breeding in high-quality spruce-fir headlands that presumably have similar microclimates to small islands. Habitat is unlikely to be a strong driver of distribution in the island system given that there is not a strong transition between the mainland and islands analogous to the elevational transition from northern hardwood forests to spruce-fir krummholz on mountains. However, for biotic interactions, small islands may represent high-quality breeding habitat because of the absence of a primary nest predator, Red Squirrels. We have yet to analyze our audio recordings for Red Squirrel vocalizations, but they are less common on islands further from the mainland (Goodale 2009) and, presumably, on smaller islands with fewer food resources.

One of our hypotheses is that the island system decouples the trade-off between predation risk and climate/habitat. In the mountains of the northeastern U.S., Blackpoll Warbler abundance increases with elevation until it reaches a maximum around 1,200 meters (Hill and Williams 2024). At higher elevations, abundance decreases as, one assumes, environmental conditions become less favorable to breeding (e.g., colder temperatures, sparser vegetation). In these mountain regions, the upper elevational limit of Red Squirrels reaches a maximum around 850 and 1250 meters following years without and with masting events, respectively (Hallworth et al. 2024). The ability of Blackpoll Warblers to breed above the upper elevational limit of Red Squirrels is likely moderated by trade-offs with less favorable climate and habitat. In the island system, Blackpoll Warblers can mitigate Red Squirrel predation by breeding on small offshore islands rather than the mainland coast, and instead of trading-off with their climate and habitat optima by doing so, these environmental variables are just as favorable on small islands. A win-win! This hypothesis may come across as a ‘just-so’ story; after all, Red Squirrels are nest predators of many songbirds and they have not all retreated to breeding on islands. However, Blackpoll Warblers are especially sensitive to Red Squirrel presence, as evidenced by the steep declines in nest success when Red Squirrel abundance increases after tree mast years (Hallworth et al. 2024). Not only does this predator impact nesting success, but Red Squirrel site occupancy has a strong negative effect on Blackpoll Warbler site occupancy as well (Warkentin et al. 2025). While the site occupancy of numerous other songbird species exhibited similar responses to Red Squirrels, it was notably strongest in Blackpoll Warblers.

As the project works towards answering some of these questions, surveys and bioacoustic analyses over the next several field seasons will focus on understanding: 1) which small islands do Blackpoll Warblers breed on; do they return annually; how do island characteristics compare to small islands where Blackpoll Warblers do not breed; 2) which islands are Red Squirrels present on; and 3) are Blackpoll Warblers truly not breeding on large islands and coastal mainland sites.

References

Bond, J. 1971. Native Birds of Mount Desert Island. Second ed. Academy of Natural Sciences. Philadelphia, PA, USA. 29 pp.

Goodale, W. 2009. Distribution of breeding birds on Maine Coast Heritage Trust Properties. BRI report number 2009-03. Submitted to Maine Coast Heritage Trust. BioDiversity Research Institute, Gorham, Maine.

Hallworth, M.T., A.P.K. Sirén, W.V. DeLuca, T.R. Duclos, K.P. McFarland, J.M. Hill, C.C. Rimmer, and T.L. Morelli. 2024. Boom and bust: the effects of masting on seed predator range dynamics and trophic cascades. Diversity and Distributions 30:e13861.

Hill, J.M. and D.M. Williams. 2024. The State of the Mountain Birds Report: Northeast 2024. Vermont Center for Ecostudies, White River Junction, VT. https://mountainbirds.vtecostudies.org/. Accessed 6/5/2025.

Knight, O.W. 1908. The Birds of Maine. Charles H. Glass and Company, Bangor, ME, USA.

Palmer, R.S. 1949. Maine Birds. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard College, vol. 102, Cambridge, MA, USA.

Ralston, J., A.M. FitzGerald, S.E. Scanga, and J.J. Kirchman. 2019. Observations of habitat associations in boreal forest birds and the geographic variation in bird community composition. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 131:12–23.

Vickery, P.D., C.D. Duncan, J.V. Wells, and W.J. Sheehan. 2020. Birds of Maine. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, USA.

Warkentin, I., J. McDermott, and D. Whitaker. 2025. Associations between elevation, introduced red squirrels, and boreal bird distributions on Newfoundland. Journal of Field Ornithology 96:6.

Share

Learn more about

The Coastal Songbird Project

Read about the project, see the latest news,

and explore the Motus tracking maps.

Blackpoll Warbler | Logan Parker