31 December 2024

Jordan Chalfant photo

It’s been a busy year for Maine Natural History Observatory! We’ve been diligently studying seaweed on the Coast of Maine in preparation for our upcoming field guide. If you’re curious about what it takes to create a field guide, here’s a recap of how far we’ve come, our 2024 accomplishments, and where we’re headed from here.

Our first endeavor in producing the guide was to figure out what species of seaweed are found in Maine. We began compiling records from published papers, herbarium vouchers, unpublished observations, and multiple existing databases into one centralized database. In 2024, we added approximately 50,000 entries to our database. Generating a species list for the State was not as simple as hunting down records though. Glen designed a synonymy tracker so that we could distinguish all the species that have changed names, sometimes numerous times, over the past 150 or so years of study. For example, Polysiphonia harveyi was renamed Neosiphonia harveyi in 2001 and renamed again to Melanothamnus harveyi in 2017. Even more confoundingly, using DNA barcoding to distinguish seaweed species is a recent development, and it continues to rearrange our understanding of the relatedness of species, resulting in more name changes. Additionally, this new molecular data has revealed cryptic diversity within numerous seaweed species, meaning that what we thought was one species based on its morphology, is turning out to be two, three, sometimes as many as six different species that seem to be identical. As scientists study these new species further, features that discern them will likely emerge, but since we hope not to take decades to release our field guide, we have to make case-by-case decisions as to how we treat these new developments.

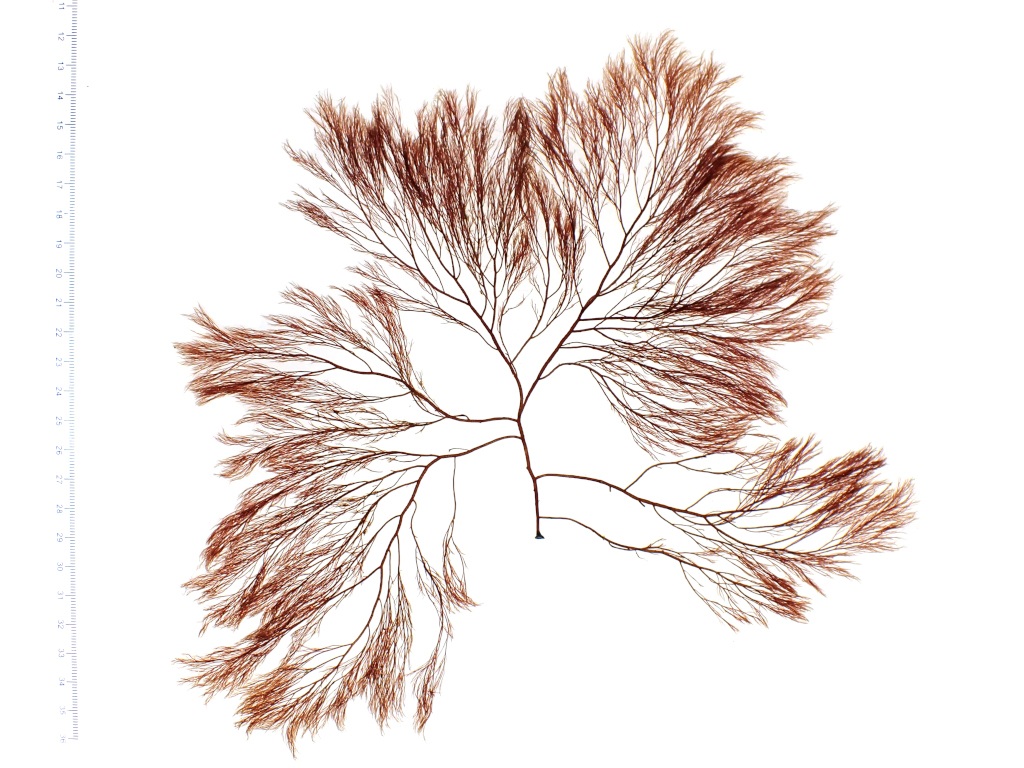

Another fun but confounding component of generating the species list and deciding what to include in the guide is that I keep encountering new species that hadn’t previously been recorded in Maine! Some are introduced, non-native species such as Daysiphonia japonica and Antithamnion sparsum. But others are more exciting. For example, in September of this year I found a seaweed that hasn’t been documented in the Northwest Atlantic for over 40 years, and had previously never been genetically analyzed! We will reveal more about this species soon, but here are some sneak peeks of the sweet little beauty.

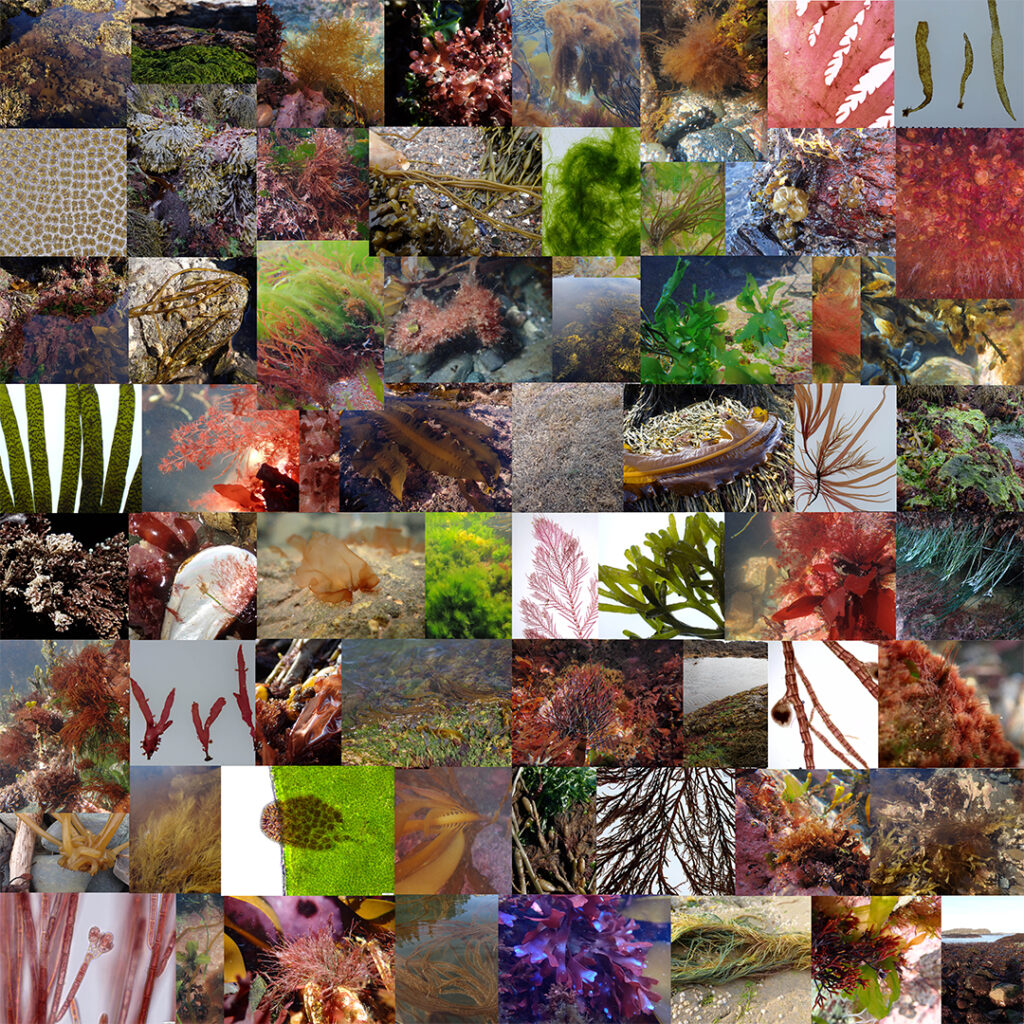

To me, the most valuable component of our field guide will be the photographs. It is difficult to find images of Maine’s seaweed species that are reliably identified and cover the scope of morphological diversity within species. I’ve been working on photo-documenting seaweed for eight years, and I now have a collection of more than 20,000 images, over 5,000 of which I added this year.

Part of the reason there are so many gaps in the scientific knowledge of Maine’s seaweed biodiversity is that there are only small windows of time when they’re accessible. Our colleague and coauthor Dr. Amanda Savoie is a diver and has contributed data from numerous dives in Maine, as have scientists before her. But most of our work is done from land, which means we have to wait for tides that are low enough to reveal the full breadth of intertidal seaweed diversity. Also, the ocean is dangerous, so weather conditions have to be suitable. Despite these challenges, in 2024 I spent more than 42 low tides documenting Maine seaweeds during every month of the year. Now that we have established a (albeit tentative and ever-evolving) species list from which to work, I’ve been able to hone in on the species we haven’t yet documented, revisiting locations where they were historically recorded. We only have a few species left on our target list. These are some of the elusive ones that we’re on the lookout for: Bryopsis spp, Gayralia oxysperma, Kornmannia leptoderma, Percursaria percursa, Punctaria spp, Planosiphon spp, Aglaothamnion halliae, Boreophyllum birdiae, Dasya baillouviana, Fimbrifolium dichotomum, Grateloupia turuturu, and Grinnellia americana.

Let us know if you encounter them!

Also in 2024, we undertook some seaweed “side projects” that have helped inform the guide. With support from the Eastern Maine Conservation Initiative, Maine Natural History Observatory conducted seaweed inventories on Anguilla and Double Shot, two ecologically-important and privately-managed islands offshore from Roque Bluffs in Jonesport, Maine. We documented approximately 78 species of seaweed on Anguilla and tracked changes in species composition and abundance over the course of the Spring, Summer, and Autumn seasons.

Just like plants, seaweed populations change depending on time of year, and this seasonality can be important for identification. Some are perennial, like many of the kelps, others are more ephemeral annuals, like the Acrosiphonia genus, which can be prolific in Spring and disappears later in the year. The majority of data on seaweed phenology was collected outside the State of Maine, and is therefore not necessarily applicable to our area. Also, climate change has been shifting the seasonality and distribution of seaweeds, as it has been for most other biota. Our Anguilla study, and others like it, will allow us to convey information that is up-to-date and specific to our region.

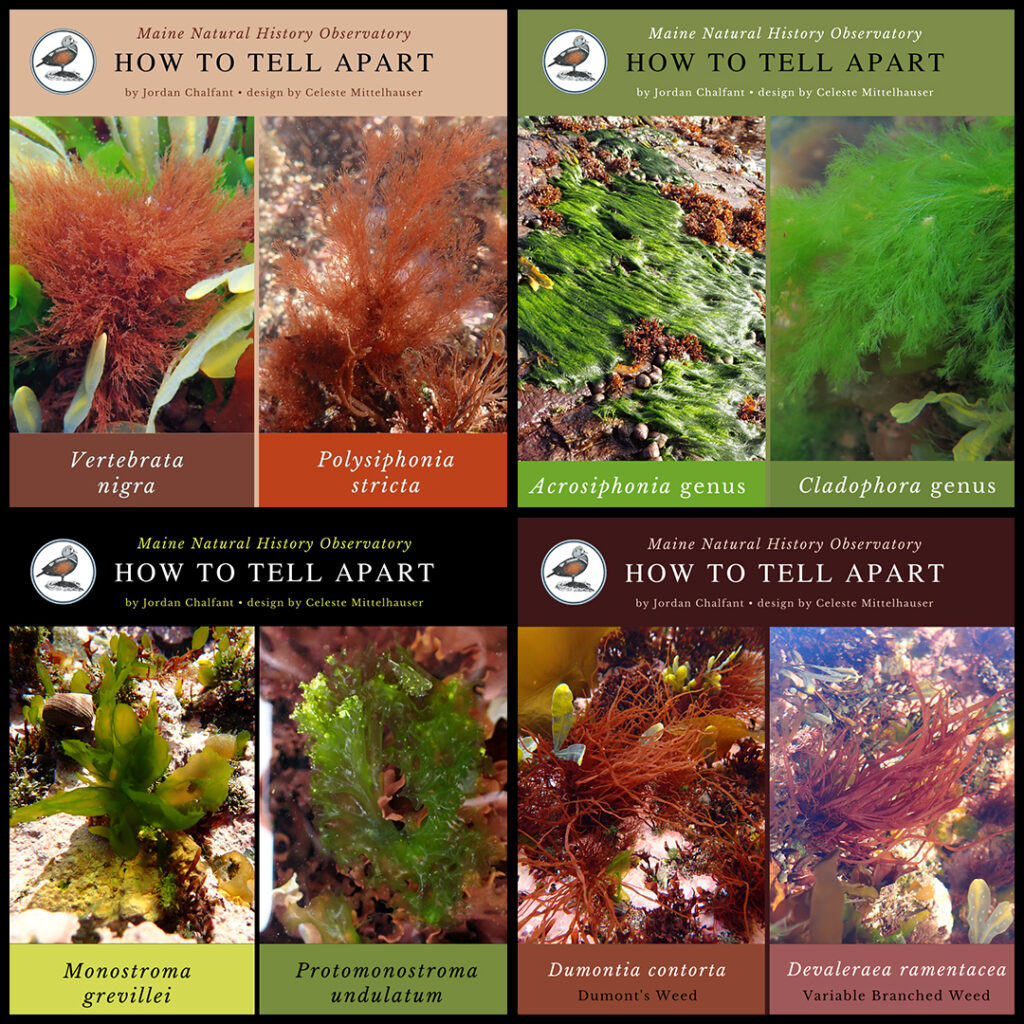

Alas, producing a field guide is not all mucking around in the intertidal. There is a LOT of writing involved. While we are researching and writing species descriptions for the guide, graphics design genius Celeste Mittelhauser and I have been producing infographics that act as simplified versions of the information that will be in the guide, helping us test out the reliability of characters and how best to present them. So far this year we’ve covered eight new species/groups with eight more well-underway. I hope you’re excited about brown algal blades, because you’re about to learn a whole lot about them over the next few weeks…

Our focus this winter will be on continuing to write species descriptions and laying out the guide. But a few other seaweed-y things happened in 2024 that are worth mentioning!

In April, I attended my first Northeast Algal Society conference and was awed and inspired by meeting some of the world’s foremost phycologists (people who study algae). It was so gratifying to make connections with some of these experts, who have continued to be generous with their knowledge and time as I pester them with questions. Thank you Gary, Craig, and Chris!

In June, Amanda led a week-long seminar at Eagle Hill Institute, all about Maine seaweed. I got to be her assistant for the second time (after having taken the class three times prior), and next year, we’ll be co-teaching “Marine Macroalgae: Ecology, Distribution, and Importance,” June 15th – 21st! More information will be available on Eagle Hill’s website if you’re interested in taking the “deep dive!”

We are hopeful that our field guide will be published in 2027. Cross your fingers– there are a lot of moving pieces! In the meantime, if you have any seaweed mysteries, feel free to send me pictures– I love a good ID challenge. Take advantage of all the free identification resources on MNHO’s website and social media pages, and let us know how they worked for you. Your feedback will help make our field guide even better. And consider joining Amanda and I at Eagle Hill next June!

– Jordan Chalfant

For questions and contributions, contact: jordan@mainenaturalhistory.org

Share

Learn more about

The Seaweeds of Maine Project

Read about the project, see the latest news, explore the maps,

and see the latest owl observation numbers.

Membranoptera fabriciana | Jordan Chalfant

Related Content

-

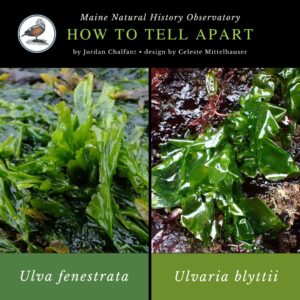

Ulva fenestrata vs. Ulvaria blyttii

by Jordan Chalfant

-

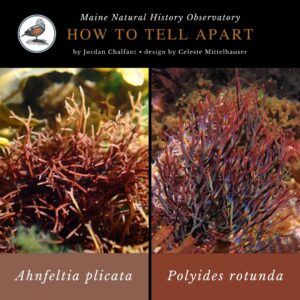

Ahnfeltia plicata vs. Polyides rotunda

by Jordan Chalfant

-

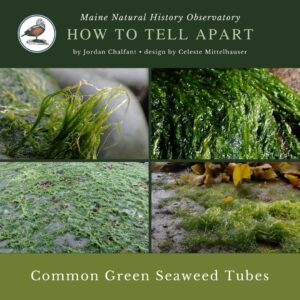

Common Green Seaweed Tubes

by Jordan Chalfant