24 October 2025

Northern Saw-whet Owl migration in downeast Maine typically peaks in mid-October. When a night with clear skies and light northwest winds follows days of poor migration conditions, particularly high numbers of birds can move across the state. We saw this pattern play out after our last update on 13 October. Of the 107 saw-whets captured since then, 103 of them passed through Petit Manan Point in just 3 nights of mist-netting, when conditions were optimal for an owl pile-up. On 18 October, we had our biggest night of the season so far, catching 53 individuals under the haze of the Milky Way.

We also had a busy human night on the 18th, with a visit from the Downeast Audubon Young Birders Club. We were excited to introduce these young birders to the station and show them how avian research is conducted in the field, and how an interest in birds can be more than a hobby. It was delightful to release owls with people who had so much joy and awe for this personal encounter with a wild animal, with wonder at the softness of their feathers, the warmth of their bodies, and their ability to look up at the sky and re-orient themselves.

A night with a steady flow of birds is a good time to see individual variation: from left to right, a

small male, two medium-sized females, and a large female. The smaller of the two birds on the

right weighed one gram more!

Owl migration banding is a testament to the importance of long-term monitoring. Years of gathering data from the same locations with standard protocols allow biologists to understand the drivers and trends of saw-whet reproductive success, juvenile and adult survival, and migration. Saw-whet breeding habitat is particularly inaccessible, and saw-whets can change their individual breeding sites annually based on prey availability. Studying these birds as they migrate is the only real glimpse into their lives. Opening nets and recording the age, sex, and body condition of the birds we capture can tell us about their population size, the pressures these birds face, and the routes they take.

We monitor how saw-whets move in both low-tech and high-tech ways. On the low-tech end, we band each bird with a uniquely numbered leg band in the hopes that they are recaptured at another station, though their path there will remain a mystery. On the high-tech end, we have outfitted a select few owls with VHF nanotags, which can answer the question of where birds go and when in much more detail by pinging off Motus radio towers. In 2025, we have recaptured four birds that were banded in the fall of 2024 as hatch-years. Two of these birds were banded at Petit Manan Point, and the others at stations in Rochester, NY, and at Hawk Mountain in Pennsylvania. We also heard from a banding station in Berlin, MA, where they recaptured a two-year-old female on 18 October that we had banded on 4 October. In two weeks, she traveled around 300 miles! We also finished putting out our 15 VHF nanotags—12 on females and 3 on males—that should tell us more about the routes birds are taking as they continue their fall migration, where they spend the winter, and hopefully how they make their way back to the breeding grounds as well.

While our focus is saw-whets, we also target several larger species. We were thrilled to capture a Long-eared Owl early in the season—the first at the station since 2021—and we were even more excited to find another in our nets on the night of 17 October. Each of these birds is a singular beauty! The 18th brought another large owl into our vicinity, but this one posed more of a threat to the saw-whets: a Barred Owl. Most of the Barred Owls captured at Petit Manan Point are hatch-year owls dispersing from their natal sites. The lack of a resident pair of Barred Owls is one of the things that makes Petit Manan Point a particularly good place to safely lure in saw-whets. The individual that showed up near our nets on the 18th stuck around for the next few days of southerly winds, and we were able to catch it on the 21st. This hatch-year Barred Owl weighed 660 grams—more than twice the weight of a Long-eared Owl or about as much as seven saw-whets!

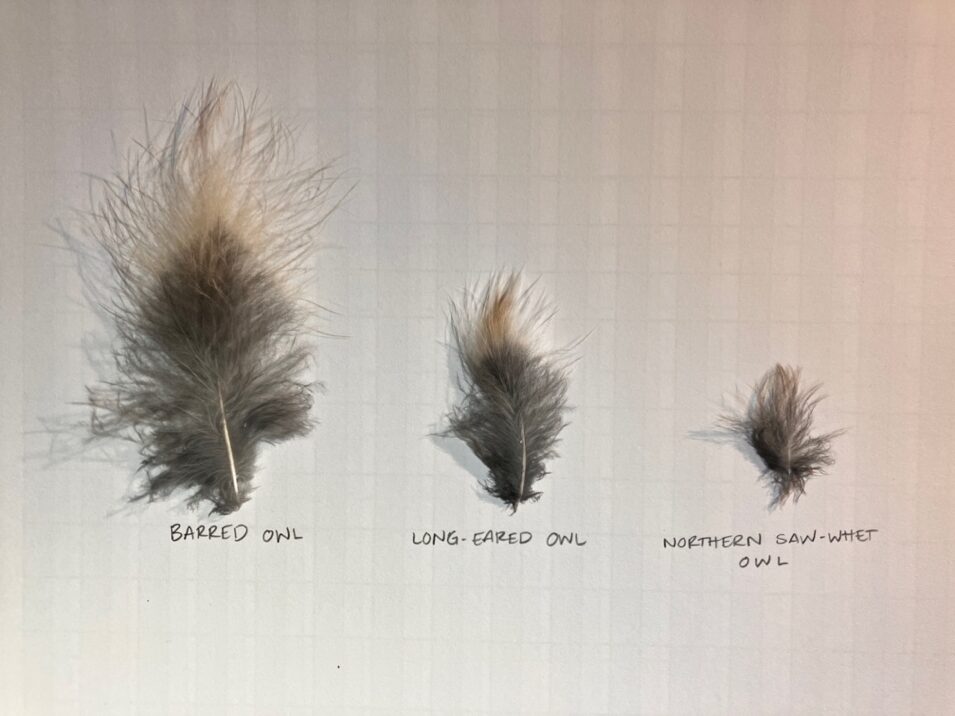

The Barred Owl on the right, and a closeup of body feathers from a Barred Owl, a Long-eared Owl, and a Northern Saw-whet Owl on the left. These downy feathers keep birds warm in cold climates.

Our season total stands at 269, a surprisingly high count following a peak hatch year when the final tally of 314 fell short of other “big years”. The next two weeks will be interesting: if the trend of high capture rates continues, it is possible that we could end the season with more birds banded than in 2024. With unfavorable conditions since the 19th, and north winds forecast next week, we are hoping for another pulse of birds before the end of the month. The large number of owls moving this season may be a result of higher-than-average overwintering survival rates, or it could be driven by more favorable weather patterns pushing birds our way. Likely, it is a combination of several factors that impact survival and movement. Our understanding of fall movement patterns in 2025 will develop as migration continues, and we start to see the data from the whole network of stations banding saw-whets along the route of their migration, from Canada to Georgia.

- Coco and Tracey Faber